DAMASCUS, Syria - It was somewhat chilly when we stepped out of our car on al-Rasheed Street in Damascus earlier this week. We saw several bearded, armed men sitting around a makeshift campfire. They must be guarding an important place, I thought. I'm accompanied by a local guide, what we call a fixer in the journalism world, and a driver. "That's Bashar's house," the fixer said.

"We need to get out," I said. "Let's see if they let us get inside."

As soon as we got out, the armed men stood up, hands on their rifles, looking alert. I introduced myself as an American journalist who’s originally from Iraq. The armed men, who belonged to Ha’yat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a group which used to be an al-Qaeda offshoot, smiled and became more cordial. This is something I've noticed in the country since arriving here a few days ago. The fighters are extremely journalism-friendly. They smile and encourage us to film anything and everything. It appears to be an intentional policy from the group as increased coverage will garner it more exposure and potentially international legitimacy. HTS, which has declared itself an independent group, continues to be listed as terrorists by the United States and the EU.

This palace, the guards confirmed, was a private mansion that the Bashar al-Assad family frequently used. It was adjacent to the house where Bashar’s father, former president Hafez al-Assad, lived. After his death, it was turned into a memorial, but it was not open to the public, according to my local friends. About 3.5 miles or a 10-minute drive from the presidential palace, Bashar’s mansion looked massive and opulent.

Nobody had asked me for a permit to film in new Syria, that is, until this very moment. The guards said for them to be able to give me that rare access, I had to have a specific permit from the Ministry of Media. It was already late for the day, but the next day I was determined to go get the permit.

The Ministry of Media building was standing, but from the inside, it was dark and dusty as if nobody had been there for weeks. It also looked eerily empty. On the first floor, there was no one to be seen. On the second floor was a foreign TV crew that spoke English with some kind of European accent. They directed us to the right room where we got our permit sent to us electronically as a PDF via WhatsApp.

We returned to the mansion through the busy streets, passing by the burnt-out building that used to house the immigration and passport authorities. Some defaced or torn pictures of Bashar were left on banners along the road. We returned; the HTS fighters still tried to prevent us from getting inside the building because the permit was not specific enough to that building, but after a bit of insisting, we were kindly granted permission to explore Bashar’s private sanctuary, hoping to see some remnants of his personal life to learn something about his tastes, his family, and why he acted so ruthlessly, killing over half a million people with no apparent qualm.

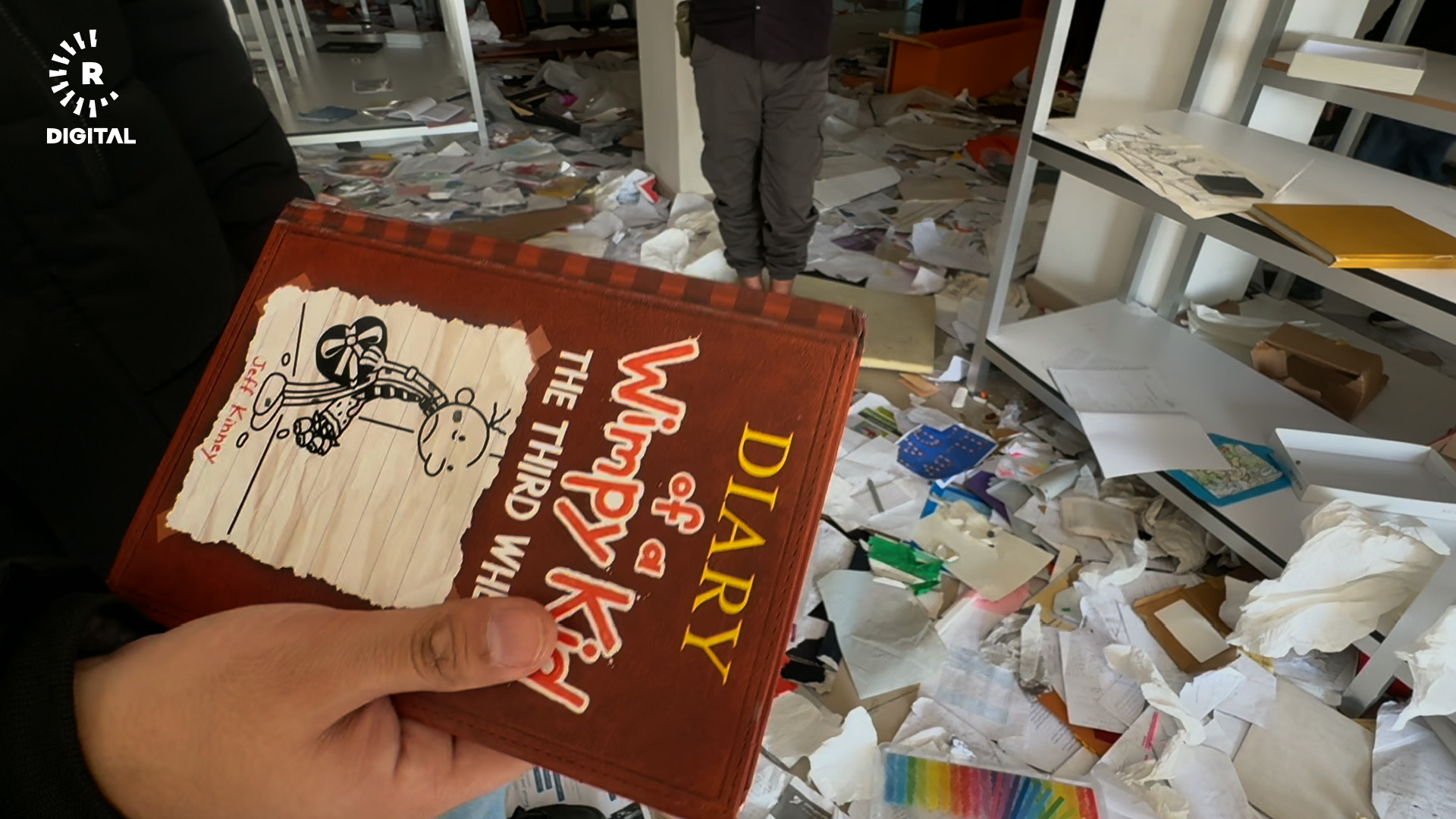

A guard opened the two-sided door for us and guided us inside the house. I took my iPhone out and started filming. The first thing I noticed was how it must have been looted. There were tons of documents and books scattered across the floors of the rooms, with broken furniture everywhere. The remnants of a pink couch and ottoman, along with a white couch, armchair, and a black stand, were left on the first floor.

At first, the house appeared so disheveled that it was hard for me to see its grandeur, which assaulted the senses. Brown hardwood stairs and floors were polished to a shine, a stark contrast with the bumpy, scarred, and broken and neglected streets of Damascus. With all its tall trees around the house, it looked like a forest, another irony in a country where trees were often cut down for firewood during the harshest winters of the conflict, just like how the guards outside were warming themselves.

I ascended the winding U-shaped, brown staircase with its glass balustrades and stainless steel handles. There was even an elevator, which was not working now due to a power outage. Having an elevator in a personal residence perhaps says something about the scale of the mansion and the value that the Assad family placed on convenience. Everything in this house seems to have been designed to create a lifestyle of maximum luxury and ease.

To be honest, this mansion was not too extravagant for a president, particularly one from the Middle East. The problem is this was not the only mansion he had. He had quite a few more in addition to the grand presidential palace. And this stood in sharp contrast to life elsewhere in Syria, where the average salary for public servants had declined to merely $20 a month in recent years.

While filming inside, I noticed the HTS security guard, who looked particularly young and didn't have as much beard as the others I've seen. He was wearing plain grey pants, a black shirt, and a backward baseball cap. He had black sandals and a handgun inside a green case on his right.

As I turned around, the guard tapped me on the back. He wanted me to film a picture he picked up from the ground. The dusty picture showed Bashar in a white shirt and his son Hafez, wearing a blue T-shirt with the top button open, looking as tall as his dad. They were wrapping hands around each other's shoulders. Bashar's wife Asma's head stuck out underneath their arms like in a photo cutout. All three had wide smiles showing their teeth.

Here, the Assads lived among volumes of religious, political, historical, and children's texts. These included the multi-volume book, "Al-Ansab," by Imam Abu Sad Abdulkareem al-Samani. This book is widely seen as the most comprehensive genealogical work focusing on the lineages, tribes, and family connections of Arab and Islamic figures, particularly those during Prophet Muhammad’s era.

For some reason, everything in this house almost instantly made me think of something else. The second floor, for example, was a mess of papers. The messy floor made me think of the chaos Assad's rule helped bring upon Syria. The white, minimalist yet elegant bathroom on this floor, with its custom-made furniture and dual toilets—one a bidet—along with the elevator and all other luxuries, made me think of Mohammed Basr al-Safadi's house deep within all the rubble that airstrikes had left, ten minutes' drive from here in the Damascus neighborhood of Tadamon. Nothing warns you about the existence of a livable space here except for a small black door within two walls of scratchy concrete. The roof is covered with rubble. This is all left from a three-story building and he turned it into a house for his family, Mohammed told me recently while holding his two-year-old daughter with his left hand. He lost his right hand from above the elbow in a Syrian government strike in 2011, he said.

The crunching sound of our footsteps on paper echoing through the corridors reminded me of the silence the government sought to impose on its populace through some of the most brutal methods. Then I saw a more recent document. Dated 2023, the hardcover appeared to be an Arabic translation of the college thesis of Bashar's son, Hafez, to Moscow State University. The title was about integer numbers and polynomials in mathematics, which he, in media interviews, has described as his “childhood passion.” And this made me think of all the Syrian refugees whose academic dreams were disrupted by conflict and who had to flee to neighboring countries like Iraqi Kurdistan and Turkey to live in tents.

Then, as we took the winding stairs to go up to the third floor, I saw a book on learning Russian for Arabic speakers. And this, along with several other Russian-language books and documents I saw inside the house, pointed to the deep political and family ties Assad had built with Russia, a relationship that may have cost Syria its sovereignty but at least got him and his immediate family members political asylum when push came to shove earlier this month.

The whiteboard included scribbling that covered both matters of heart and mind. “Love you” + a heart drawing + a smiley face, Basel,” was written in black on the board. Above that was some basic math techniques like “15X15 = 10X10 +5X5,” which appeared to have been the work of Hafez. Then I saw the house’s largest bathroom with a custom-made bathtub that appeared to have been an integral part of the concrete building.

From the balcony, I looked over a manicured garden, with its triangle of soil and shrubs, trees as tall as the building itself. It was a green oasis but there was little grass in the house. The only patches of grass were the kind that required no maintenance. I waited on the balcony for a minute to get some fresh air. After heading back inside, I saw the hardcover version of "Diary of a Wimpy Kid," a series of children's novels by Jeff Kinney. This immediately made me think of Alan Kurdi, the two-year-old Syrian-Kurdish boy who drowned while attempting to escape Assad’s Syria for a better life in Europe

The top floor was nearly empty, save for a few documents, with a large power generator and several tanks, each the size of two large refrigerators, appeared to have been used to store water and gas for the house in an attempt for self-sufficiency in a nation where public services had crumbled. The generator’s doors were open, revealing intricate wiring. It looked like looters had opened the doors but found nothing particularly valuable to steal from a generator which was too heavy to move. The rooftop also included three satellite dishes facing different directions.

Then I saw something that I didn’t expect: tunnels. There was a tunnel under the building. I must have walked for a couple of hundred meters inside the tunnel before reaching a dead-end, a locked door. The iron door of the tunnel looked like those vault doors that banks have, and this spoke of how paranoid the Assad family was, living in fear of its own people, all the while he had instilled fear in every household across the country. Another example of Assad’s paranoia was the day he fled Syria without informing his close family members including his brother Maher, who struggled to make it to Iraq via a helicopter at the last minute then to Russia, according to Reuters. This paranoia of the Assad family is not something new. It can be traced back to Bashar’s father, Hafez, and his iron-fisted rule, including the 27-day brutal crackdown on protesters in Hama in 1982 when at least 10,000 of his own countrymen and women were killed.

We headed down from the rooftop, I saw playing cards and several copies of celebrity magazines like Anna, Burda Style, and Susanna. A score sheet included recognizable names like Asma, and Zien, their daughter. The family appeared to have created a life of luxury for themselves when poverty in the country had reached catastrophic levels: more than 90% live below the poverty line, according to a 2022 UN report. A math book on the floor was open to its dedication page, reading, “to our beloved Syria and all the honorable who one day believed in it."

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment