Three years ago, Saide Inac, better known by her stage name Hozan Cane, was excited to travel to Turkey to support her fellow Kurds during an election campaign. Leaving her home in Germany, the Kurdish singer flew to Turkey on June 11, 2018 to endorse the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), which was looking to pass the 10-percent threshold required to enter the parliament.

Cane ended up imprisoned for more than two years where she was subjected to violations of almost every right. But she did not let this ruin her life. Instead she turned her time in prison into a school - thanks to other prisoners she calls “philosophers.”

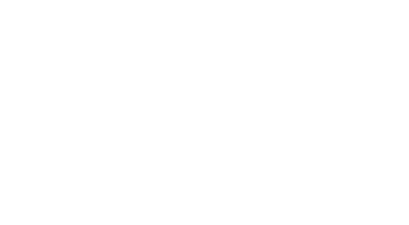

A few days before the June 23 vote, Cane went on stage in Edirne city, singing in Kurdish and wearing traditional clothing. “As a Kurdish artist, I wanted to help them [HDP]. If there is an election in any part of Greater Kurdistan, as a Kurdish artist I can go there and sing for people. This is my artistic right,” the 48-year-old told Rudaw English via Skype. Greater Kurdistan refers to Kurdish areas that stretch across the international borders of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria.

Around 2am on June 22, Cane and around 50 other HDP supporters were traveling by bus to another rally in Edirne when they were stopped by Turkish gendarmerie. “When the door of the bus opened I saw someone calling my stage name, Hozan Cane. I did not identify myself, thinking they only knew my stage name. Their general then said to a soldier ‘Saide Inac’ - my official name.”

She knew she was in trouble with no way to escape. Staying silent would not help her, so she identified herself. She was wearing Kurdish traditional clothing, which she usually wears when performing. “They detained me. I asked the commander why they asked for my ID among 50 people,” she said.

While speaking to the commander, Cane was searching for ways in her mind to hide some items she was carrying. “I had my Germany mobile with myself, which contained a lot of photographs taken in Bashur [Kurdistan Region] and Bakur [southeast Turkey]. A Yazidi woman from Cyprus was with me on the bus, helping me. I put my mobile in the upper part of her Kurdish dress. I did this while blocking the eyes of the soldier with my elbow,” she said.

The soldiers did not notice. They led her away handcuffed to a small military post on a mountain, half an hour away from Edirne. Up to 100 soldiers were guarding the post.

The bus, driver and the passengers were all allowed to leave. Cane remained alone in the hands of the soldiers.

Born in Karayazi district in Erzurum province in 1973, Cane dreamed of becoming a singer. Her father died when she was four and her mother raised Cane as well as her four sisters and four brothers. Her mother was not on good terms with her brothers-in-law and they repeatedly made problems for her.

“My mother wanted to marry off her daughters at an early age because honor was really a thing in our area,” Cane said. So her mother married off her daughters between the ages of 9 and 12.

Cane married at the age of 11. When her husband married a second wife, Cane abandoned him, fleeing to Istanbul where she began singing on stage in 1991. She sang in Kurdish, despite a ban on the language. Two years later, she migrated to Germany and her daughter joined her in 1997. They built a new life in Germany where Cane performed at weddings and parties and her 35-year-old daughter is a psychology graduate.

Cane in jail

After the bus left, Cane was left with the all-male soldiers. Police found three US flash drives in her bag. She said just one was hers and the other two were put in the bag by some people without her knowledge.

“At 4pm, they put me in solitary confinement in Edirne for nearly a week. They later took me to court, which decided to send me to a prison in Edirne,” said Cane.

Four days after she was detained, former HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtas, who has been jailed in Edirne since November 2016, sent her a lawyer. She had not had access to a lawyer since her arrest. Another two days later, Cane appeared in court where the judge ruled she be officially arrested.

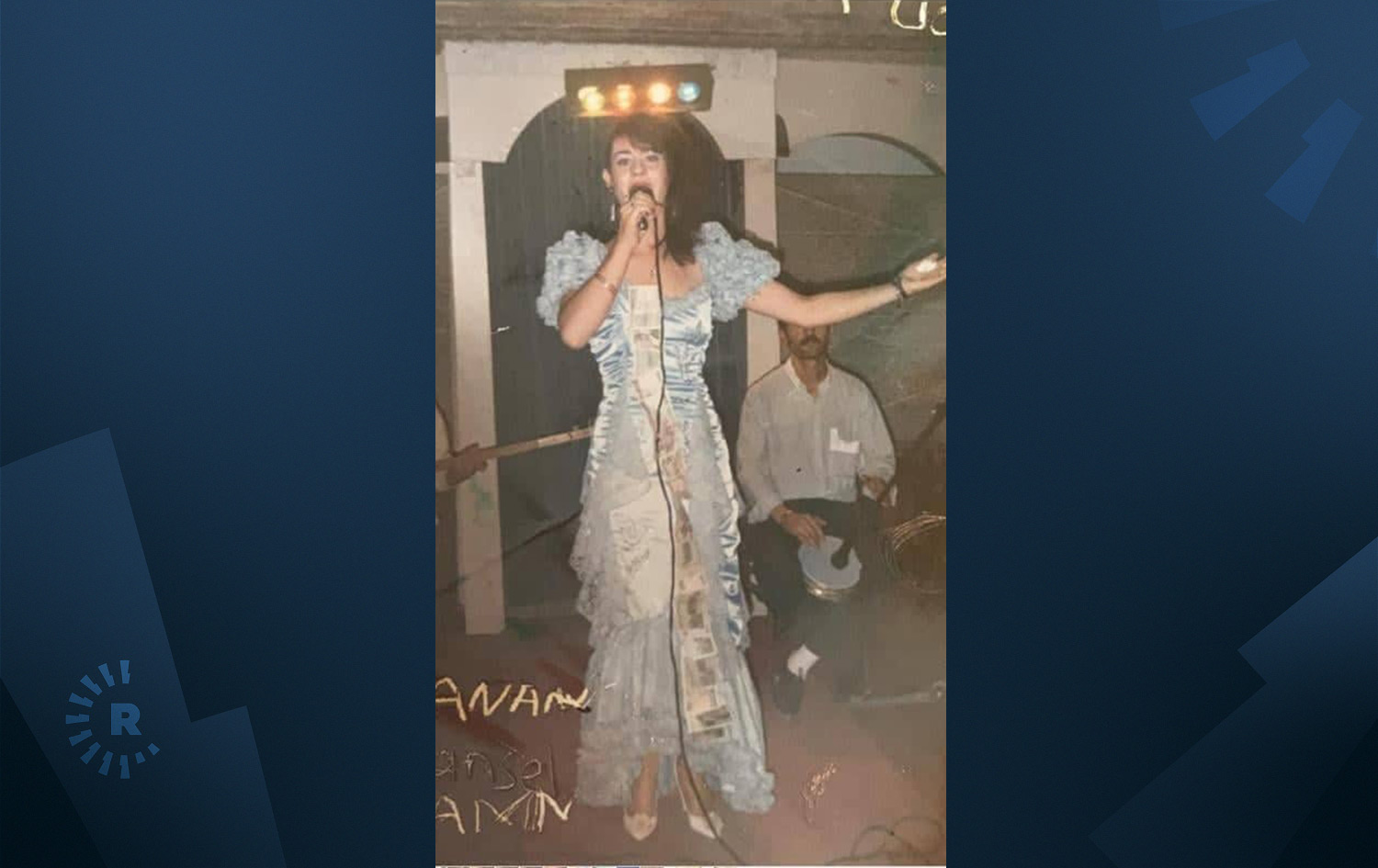

She was accused of having links with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) - an armed group fighting for the increased rights of Kurds in Turkey. The allegations stemmed from a film she was involved in. Kurdish fighters in northeast Syria (Rojava) - who Ankara claims are affiliated with the PKK - were featured in the film and she had taken photographs with PKK commander Murat Karayilan.

“The USB flash drives contained my photograph with Murat Karayilan,” Cane said, adding that the picture was taken by a Turkish news outlet on Mount Qandil during the 2014 peace process between Ankara and the PKK. Cane was part of a group of artists, journalists and politicians who visited the PKK headquarters.

After the court ruling, Cane was sent to maximum security Edirne F-Type Closed Prison.

“When I was moved to Edirne prison, I was treated very badly by female prison guards. One held my head and one held my shoulders, and began the strip search. They also did worse things like putting their hands in women’s vaginas… The search was really terrible - as if they had captured a lion or wolf and dismembered it,” recounted Cane.

She was put in a cell with 15 women and their children, affiliated with the Fethullah Gulen movement. They told Cane that they had experienced worse when they first entered the jail. The Gulen movement is accused by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s cabinet of orchestrating the July 2016 attempted coup. Most political prisoners in Turkey are accused of having links with either the PKK or Gulen.

“The toilet was also in the cell and its door was always open. The smell that came from the toilet drove us mad. The hot water was allowed in for half an hour a week. How can 15 people take showers and wash their clothes in half an hour? There were also young children among us, including a two-month one and a six-month one,” said Cane, her suffering evident in the tone of her voice.

The prisoners were given a spoonful of food twice a day and a 100-gram piece of bread.

There was only one small window in the cell.

Cane lived in these conditions for about a month, until the Germans got involved. She had been banned from receiving visitors and requested Germany’s intervention. A delegation from the German consulate general in Istanbul came to the prison and Cane told them what she had suffered. “I told them that I was dying there, as there was no food or washing. The Germans spoke with them [Turkish authorities] and told them that I had to be transferred within days to Bakirkoy, Istanbul.”

Bakirkoy is a women’s prison on the European side of Istanbul.

Cane said she also told the German delegation that guards would spit in the prisoners’ faces whenever they opened the door of the cell in the evenings and she complained about the stench from the toilet.

Prison guards and administration personnel had said among themselves that they arrested “a very big terrorist,” Cane said, bursting into laughter as she described the claim as foolish. “They even called me ‘Karayilan’s assistant for Europe.’”

The singer, who has also campaigned for the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in Kurdistan Region elections, said she has never had any affiliation with any party or group, but has been a patriotic artist. “The PKK even didn’t properly show me on their TVs. They didn’t like me because I was patriotic and wanted to remain so. I really didn’t have many relations with the PKK.”

A few days after the Germans’ visit, Cane was moved. “One day at 5pm, they put me in a prison car, which itself is a jail. It’s made of steel. My hands and legs were cuffed,” she said.

While in the vehicle being transferred to Bakirkoy Women’s Closed Prison, Cane said she was forced to listen to a nationalist Turkish song, Olurum Turkiyem [I die for my Turkey]. “The song was played for four hours without interruption. Because I was handcuffed, I could not block my ears. So, I would block one ear for a while then block the other. This was four-hour systematic torture.”

The song by Mustafa Yildizdogan was first sung in 1993. Cane said the music was so bad it sounded like “hitting a metal can.”

Arriving at Bakirkoy prison, Cane hoped she could live like a human - unlike in Edirne.

Meeting the ‘philosophers’

Her new cellmates hesitated in befriending Cane. They were Kurds too, but were different from anyone else she’d met before. “They were philosophers,” she said.

“The first couple of months were difficult as I didn’t know anyone. The cell was 25 square metres, but 60 women lived there. It contained 1.5 square metre cells with four beds, meaning four people slept there. One couldn’t even breathe well. They had tiny windows that were not enough to help you breathe. Imagine four women living in it! In winter, it was so cold that we couldn’t open doors or windows. If you open them, you freeze, but if you don’t then the odour [from the toilet] will kill you,” recalled Cane.

Her fellow prisoners were members of the PKK who had lost their freedom some 30 years earlier, so they had never heard of the Kurdish singer called Hozan Cane. After a couple of months, a letter arrived from the PKK, introducing Cane to her cellmates. The PKK asked its members to provide any possible support to Cane, probably because she was arrested due to her alleged links with them.

“After this, everything changed. They shared their clothes and food. They would eat a bit of my food first, to see if it was poisoned,” said Cane. Sometimes a substance was put in their food that would damage their health - dry out their skin, make them go bald, and affect their memory.

She described the cell as a school and select PKK members, the “philosophers,” taught her about Kurdish nationalism, history, geography, and legendary figures.

“They were medical doctors, teachers, lawyers, engineers, and historians who had been in jail for 30 years. They were really educated and skilled. They were literally philosophers.”

Cane had spent her early years in a country where education in Kurdish language or about Kurdish history and culture was banned. A large number of Kurds have been assimilated in Turkey. Many do not know about their history and culture, and are not fluent in their mother tongue. Kurdish language has been silenced in Turkey for nearly a century.

Rawest, a Kurdish research center in Diyarbakir, conducted a survey in several Kurdish areas of southeastern Turkey in September 2019, to scope out the extent of Kurdish proficiency among the country’s 18 - 30 year olds. Of the 600 young Kurds surveyed, only 18 percent said they could speak, read and write Kurdish. Less than half of respondents, 44 percent, said they were able to speak their mother tongue. When asked what the official language of Turkey should be, 71.5 percent of participants said it should be both Turkish and Kurdish.

In prison, encouraged by her PKK cellmates, Cane was able to learn her own history. She read what books were available about Kurds, though volumes related to the PKK or Kurdish nationalism were not allowed in the prison.

German diplomats continued to visit Cane, staying for hours with her in order to learn about her condition. She would tell them everything.

“My prison days were really hard. When I fell sick, they wouldn’t take me to a doctor. They also didn’t give us medicine. When they did give us medicine, it took three months. They would throw it in our faces. During searches, they tore all our clothes. They also poured our food on the ground and broke our glasses. Twice in a week, 200 soldiers would search the cells, creating a mess,” said the singer.

Many prisoners were suffering from chronic diseases.

Eren Keskin, co-chair of Turkey’s leading Human Rights Association (IHD), told Rudaw English via WhatsApp that Cane had wanted her to visit several times, but she was not permitted to have visitors. She said Cane’s rights were violated.

“Hozan Cane, like many female prisoners, suffered many rights violations. She was subjected to ill-treatment such as strip searches, verbal abuse and swearing. Despite being seriously ill, she was kept in solitary confinement. She was denied access to her daily needs. She was put on trial just because of her thoughts, because of her identity as a Kurdish artist, and she was sentenced for being a member of the organization,” said Keskin, who has spent much of her life advocating for human rights in Turkey.

“Rights violations in prisons continue intensively. Ill-treatment, strip search, blocking of books and newspapers, and the violation of the right to [medical] treatment are very intense. There are around 1,400 seriously-ill prisoners,” she added.

Rudaw English reached out to the Turkish justice ministry for comment on the alleged violations in prisons but has not received a response.

Civil Society in the Penal System (CISST) is an organization monitoring Turkey’s prisons and advocating for reforms. They said authorities do not share information about violations in Turkey’s jail. “However, based on the reports prepared by us and other non-governmental organizations, it is possible to say that there has been a serious increase in reports of violations of rights in prisons in Turkey in recent years. We can say that there has been a significant increase in reports from both judicial [criminal] and political prisoners, especially during the pandemic period,” CISST told Rudaw English via email.

Cane spent her days in prison with members of the PKK and the Gulen Movement. Asked if all prisoners are treated the same way or those affiliated with these two groups are treated differently, the CISST said, “In fact, violations are a much more general problem in Turkish prisons.” Political prisoners are targeted with “systematic practices,” but violations against the general prison population “are also very serious,” it said.

“Counting while standing, strip search, book restriction, frequent searches of the ward where the goods are distributed, are the most prominent reports” CISST said it receives from prisoners.

Freedom

After 832 days in jail, Cane was released on October 1, 2020 on condition she remain in the country. She had been sentenced to six years and three months while in jail in November 2018 for being a member of the PKK. She was tried again in February 2021 on terror charges.

She said that German authorities and politicians have told her off the record that she was released due to their intervention and that German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other top German officials discussed her case with their Turkish counterparts. She even claimed that Germany had paid Turkey for her release.

Rudaw English reached out to the German consulate in Istanbul and the German foreign ministry, but they were not available for a comment.

Her daughter, Dilan, campaigned for her in Germany, talking to the media and politicians. Her advocacy forced German authorities to prioritize Cane’s case, said the singer. “After the case was discussed in the German parliament, Merkel met with Turkish authorities three to four times… They came specifically for me… The consulate said so, but also said that they cannot reveal this to the media.”

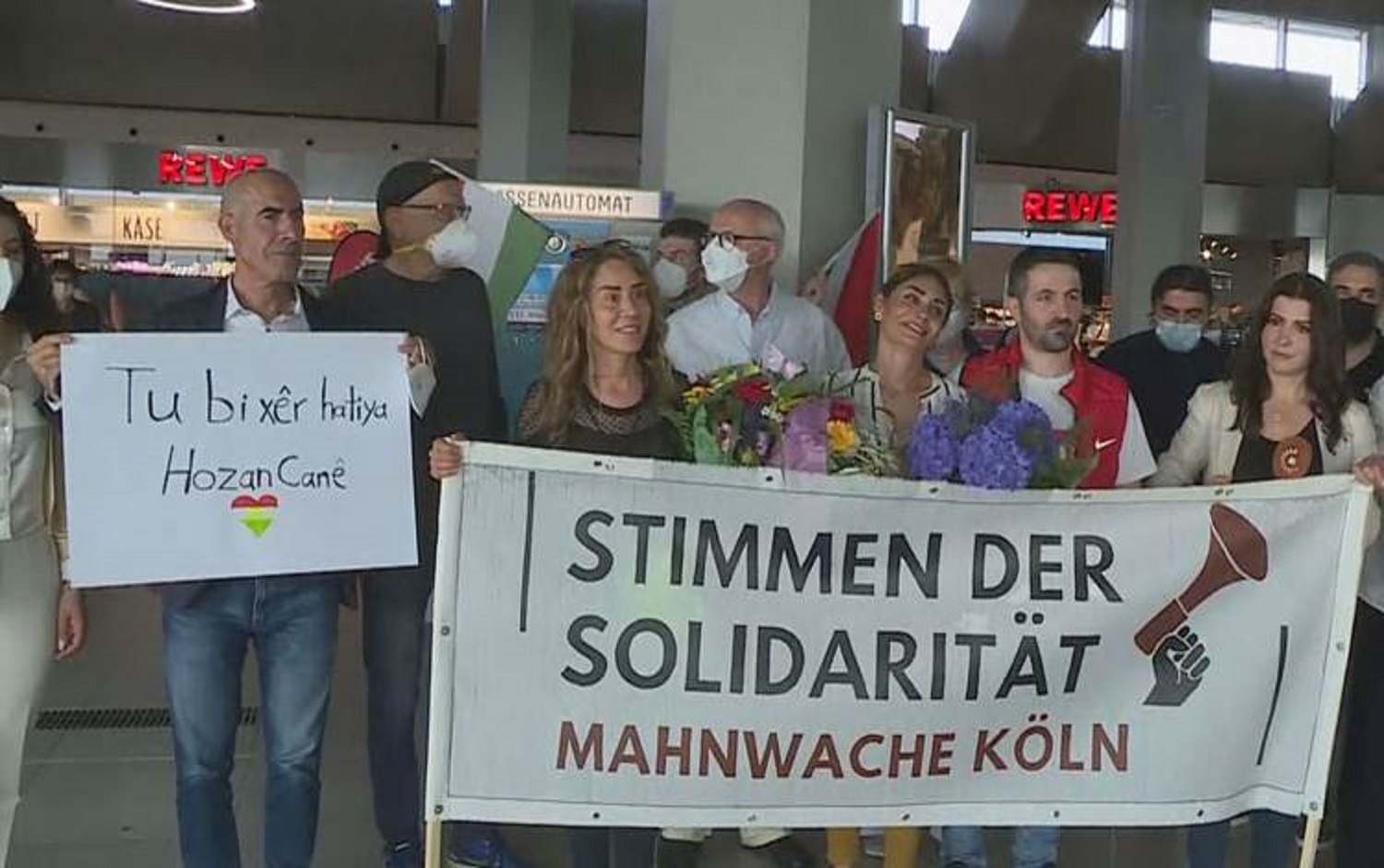

Cane was allowed to return to Germany in mid-July. Her eyes filled with tears when she landed in Cologne. "I am thrilled to have returned. As a mother, I am very happy to have seen my children,” she told Rudaw at the time.

She is trying to pick up the normal life she lost in 2018, but it is impossible for her to forget what she suffered in jail in Turkey.

Her next court date is scheduled for September 20 as her trial continues in absentia.