ERBIL, Kurdistan Region - Growing up in the mainly Kurdish city of Qamishli in northeastern Syria (Rojava), Janda Arafat could only study in Arabic because the Syrian regime had banned her mother tongue. It was not until Kurds took control of the territory in 2011 that she had the opportunity to take informal Kurdish classes. Today, she teaches the language at a university. The recognition of Kurdish as an official language of Rojava has empowered younger generations to learn and teach the language freely.

Successive Syrian regimes categorically denied Kurdish cultural and political rights and suppressed any movements that strived to promote them. Groups who wanted to teach the Kurdish language had to do so in secret for decades. When the Syrian uprising began in 2011, the regime relocated its troops from Kurdish areas to the outskirts of the capital city of Damascus to fend off attacks by rebels. This allowed Kurds to take over their land without clashing with the Syrian army.

At the time of the liberation of Rojava, Arafat had just graduated from high school. Her father, who had secretly taught Kurdish under the regime, started teaching the language openly. Inspired by the growing movement to learn Kurdish, Arafat decided to attend her father’s classes. In 2016, she enrolled in the Kurdish department of the University of Rojava and graduated two years later.

Arafat currently teaches Kurdish at the same university. She told Rudaw English in flawless Kurmanji dialect of Kurdish that Kurds should see their linguistic freedom as a “golden opportunity” to spread their mother tongue and strengthen their grasp of it. The teacher noted that there is an increasing demand from Kurds to learn their language.

Forbidden language

Syrian Kurds have been subjected to state discrimination since the establishment of the country nearly 80 years ago. They suffered from lack of political, economic and cultural rights. The Kurdish language was banned from public use. Former Syrian president Hafez al-Assad intensified the process of Arabization when he came to power and his successor and son Bashar al-Assad inherited the oppressive policy. After a 1962 state census that Human Rights Watch said was tainted with arbitrariness, thousands of Kurds were stripped of their Syrian citizenship on the grounds that they were “alien infiltrators” from Turkey. Their fundamental rights were taken away from them.

Human Rights Watch said in a special report in 1996 that denying nearly 200,000 Kurds the right to Syrian nationality constituted a “violation of international law.” It reported that the census was “one component of a comprehensive plan to Arabize the resources-rich northeast of Syria, an area with the largest concentration of non-Arabs in the country.”

“Suppression of the ethnic identity of Kurds by Syrian authorities has taken many forms. Restrictions have included: various bans on the use of the Kurdish language; refusal to register children with Kurdish names; replacement of Kurdish place names with new names in Arabic; prohibition of businesses that do not have Arabic names; not permitting Kurdish private schools; and the prohibition of books and other materials written in Kurdish,” read the report.

Despite the ban and the threat of arrest, many groups managed to secretly provide Kurdish classes in private homes. These informal classes continued until Kurdish forces liberated their territories in 2011, after which the classes were held out in the open. The informal classes only ended when Rojava authorities established Kurdish schools a few years later.

Mazloum Abdi, commander-in-chief of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the de facto army of Rojava, said in May that these secret groups played a pivotal role in keeping the Kurdish language alive, adding that he himself learned his mother tongue from them.

Abdi noted that the Syrian regime still insists in its talks with Kurdish authorities that Arabic should remain as the only recognized language in Syria, including Rojava.

“Kurdish education is always one of the pressing issues we discuss with the Syrian regime. It is a red line for us. We do not make compromises in this regard. The Syrian regime refuses this, pushing for the prioritization of the Arabic language,” he said during a video message addressing a Kurdish-language related event on May 20.

Rebirth

After taking over most of the Kurdish areas in northern Syria, Kurds established their own government, called the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES or NES). While Kurds were restoring their cultural and political rights, especially reviving Kurdish language, the Syrian regime was struggling to remain in power as rebels were seizing more land in the early years of the war that took a heavy toll on Damascus.

Samira Haj Ali, co-chair of Rojava’s education board, told Rudaw English that they heavily prioritized Kurdish education in the period right after Kurds reclaimed their land.

“We held conferences about Kurdish language, established the Kurdish Language Institute and opened Kurdish schools in many areas of Rojava such as Afrin, Kobane, and Jazira in 2011 when the regime was still strong. Later, we started preparing teachers for these schools and officially offered Kurdish lessons there between 2012 and 2014,” she said.

The Kurdish Language Institute (SZK) had been giving Kurdish classes secretly since 2007, and later became part of the Rojava administration’s education board. The SZK teaches Kurdish to students, public employees, and teachers and provides online lessons open to anyone interested.

Kurds now study in their mother tongue from the first grade of school until they graduate university. Beginning in the fourth grade, they study Arabic as a mandatory second language. Likewise, other ethnic and religious groups study in their mother tongues, and take Kurdish as a second language from year four, according to the co-chair of the education board, which operates in parallel with the education ministry.

“The Autonomous Administration was able to preserve the linguistic and cultural rights of the Kurdish community completely. This process continues,” Ali noted.

The official stressed that they do not impose Kurdish on non-Kurds, adding that some schools in Arab-majority areas like Deir ez-Zor, Manbij, Raqqa and Tabqa offer optional Kurdish classes.

She said that many Arabs have requested Kurdish lessons.

In 2016, the Rojava administration approved the Social Contract, an informal constitution of the region that aims to provide equal opportunities to all ethnic and religious groups.

“All languages in northern Syria are equal in all areas of life, including social, educational, cultural, and administrative dealings. Every people shall organize its life and manage its affairs using its mother tongue,” stipulates Article Four of the contract.

One of the key obstacles Rojava authorities initially struggled with was the lack of Kurdish language teachers. They have yet to completely address this issue.

Viyan Hassan, co-chair of the SZK, told Rudaw English that most NES employees cannot speak Kurdish, adding that they are stepping up their efforts to teach the language to all civil servants. The majority of the personnel did their education under the regime’s system.

Remnants of Arabization

Eradicating the impact of the decades-long process of Arabization in Rojava is a challenging task. Despite efforts to make Kurdish the first language of northeast Syria, a large number of Kurds opt to use Arabic on shop signs, in social media posts and during daily conversations.

Even the NES and Kurdish ruling and opposition political parties have failed to prioritize Kurdish language in all their official documents and statements.

“It is true that all official documents of the Autonomous Administration are published in Arabic. The Kurdish Language Institute aims to promote the Kurdish language in Rojava. We are trying to make all NES institutions publish their documents in Kurdish, Arabic and Assyrian - as stipulated in the Social Contract,” the education board’s Ali told Rudaw English.

“The Kurdish Language Institute is endeavouring to open its Kurdish language teaching offices in all parts of northeast Syria to help public servants and ordinary people learn Kurdish. We particularly focus on the NES employees in this process… We have decided to archive all documents in at least Kurdish and Arabic at all NES institutions,” she added.

Hassan from the SZK also acknowledged that most NES statements are published in Arabic, adding that the administration’s officials admitted during a meeting with her institute early this year that this is a “shortcoming” that should be addressed.

Since then, the NES has started adding Kurdish to statements on its Facebook page but Arabic remains as the main language. Its website is available only in Arabic.

Official documents should not be in just one language - either Kurdish or Arabic, according to Hassan. “The Autonomous Administration should not write [documents and statements] only in Kurdish because there is a large population of Arabs whom the NES addresses. Therefore, it should be in Arabic too,” she said.

Adile Evdile is a Kurdish writer. He told Rudaw English that he believes Arabic will remain dominant in Rojava.

“As long as we do not have a state, the Arabic language will remain dominant. It is a good development [that Kurdish is being taught] but Kurds are leaving [the country],” he said, adding that Kurdish has not become a dominant language because most adults use Arabic.

The NES recognizes the Kurmanji dialect of Kurdish as the official language of Rojava.

According to a survey conducted by the University of Rojava in February, 66 percent of its lecturers said they were able to teach in Kurdish, but only 40 percent preferred it. Thirty percent chose Arabic as their favoured language of instruction and 10 percent wanted to teach in English.

Rojava authorities have struggled to impose the Kurdish curriculum in many cities as some teachers refused to abandon the regime’s curriculum. Numerous teachers have been punished for failing to follow the new education system.

Fluent speakers

The majority of the young generation of Kurds in Rojava are fluent in Kurdish, thanks to a decade of education in their mother tongue. Authorities have stepped up their efforts to remove Arabic words from the Kurdish language, especially in schools and universities as well as online courses.

Lavin Batal is a sophomore at the University of Rojava’s faculty of Petrochemical and Chemical Engineering. She has been officially studying in her mother tongue since 2017.

“This was really a great development in our lives because studying in your mother tongue is really a sacred thing,” she told Rudaw English in a flawless Kurdish.

“Kurds have a rich culture. The recognition of Kurdish as an official language gives Kurds opportunities to invent many things in Kurdish,” she said.

However, she noted that faculties like hers lack specialized resources in the language. Seminars are delivered in Kurdish, but revert to Arabic when needed.

The head of the education board said the NES is working on translating these resources into Kurdish.

The SZK has not only sought to teach Kurdish but to regularize the language as well.

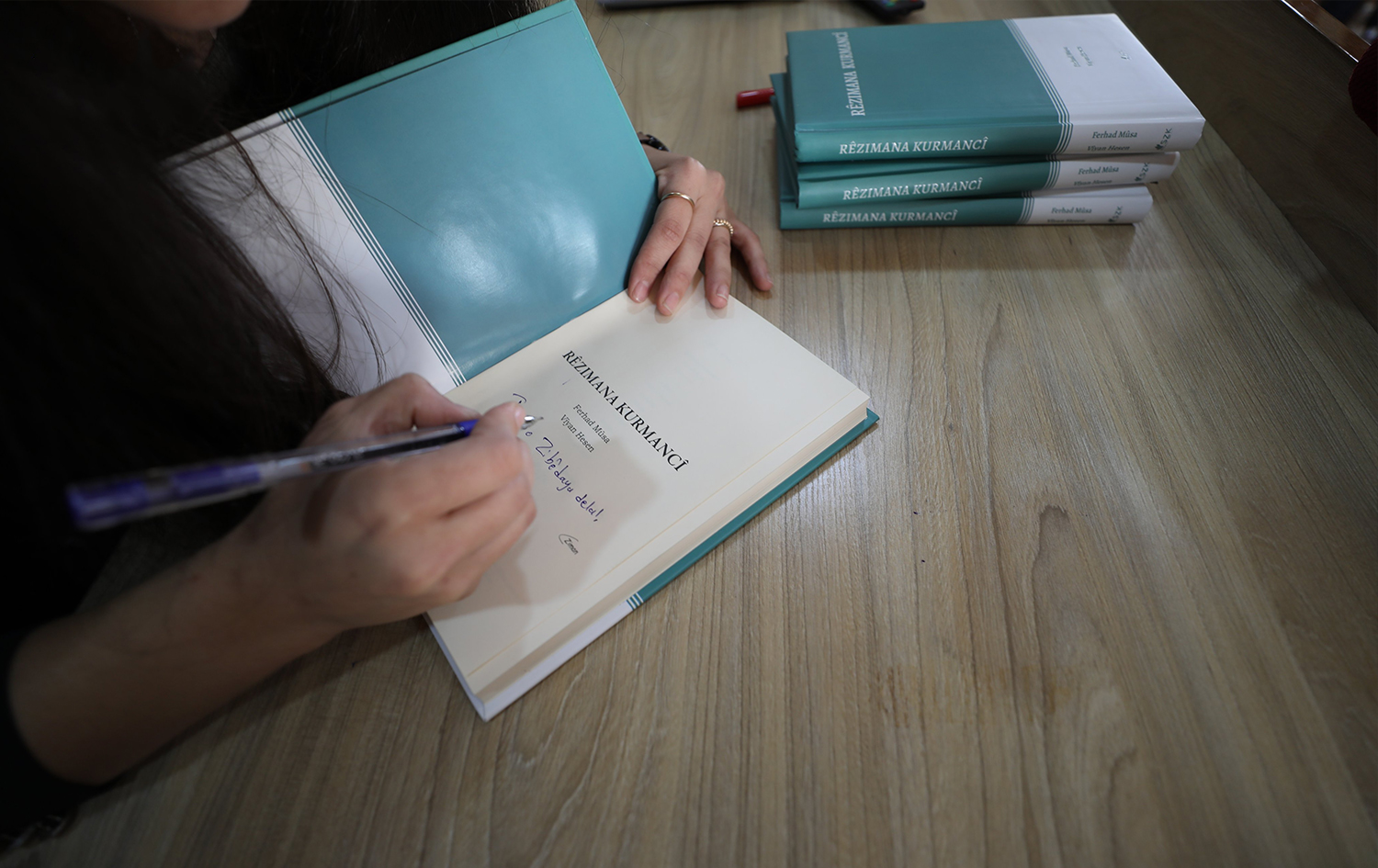

The institute’s Hassan co-penned a book, Kurmanji Grammar, published in October, that aims to standardize the rules of the language. The NES recognized the book as the main source for Kurmanji grammar.

The book was written to “regularize the texts used by the institutions in Rojava and the entire northeast Syria,” Hassan said, adding that they have called on all local media outlets to follow the book in their articles in order to ensure consistency in the use of the dialect spoken by most of the residents of Rojava.

Evdile said he has not read Kurmanji Grammar but considered its publication a “good step" towards consistency in the use of the language.

In 2019, SZK opened a research centre in Qamishli to promote Kurdish language in academic settings. Kurmanji Grammar is part of this project. They also translate texts from Badini, the most common dialect of Kurdish in Kurdistan Region’s Duhok province, to Kurmanji to provide more academic sources for universities.

“The Kurdish language is an important subject, especially during the revolution. It is one of the main dossiers we want to tackle,” SDF’s Abdi said in his May speech.

“During the Rojava revolution, we noticed the importance of language more and more. We realized that the revolution is not possible without language and vice versa. Language is the basis for many things,” he added.

There are three universities in northeast Syria: the University of Rojava in Qamishli, the University of Kobane in Kobane, and the University of Sharq in Arab-majority Raqqa.

There are also 4,614 schools with 41,507 teachers and 846,595 students in the region, according to the co-chair of the education board.

NES-affiliated organizations have also offered Kurdish language courses for elders, including in the Syrian capital of Damascus. It is not clear how such classes were allowed by the regime in the capital city.

Fate of Kurdish education

Kurdish education in Rojava is only recognized by the NES administration. For the millions of Kurds who have studied in their mother tongue, their future remains unclear. The Syrian regime has repeatedly asserted that it does not recognize Kurdish education.

“Children who have been taught Kurdish during the revolution have now grown up and entered universities. It is our duty to get the Kurdish language recognized by the international institutions and by the Syrian government. This is one of our priorities,” SDF’s Abdi said in his video message.

Elham Ahmad, co-chair of the Syrian Democratic Council (SDF), the political wing of the SDF, told Deutsche Welle that neighbouring Turkey also does not tolerate Kurdish education in Syria.

“It fears that the Kurds in Turkey might then demand the same,” she said. Kurdish is also banned in public settings in Turkey.

The first Kurdish school in Rojava was opened in Afrin after Kurds took control of the region. It was short lived. Turkey and its Syrian mercenaries invaded the city in 2018 and banned the Kurdish language. Today, education in the city is provided only in Turkish and Arabic.

The same is true for Sari Kani (Ras al-Ain) and Gire Spi (Tal Abyad) - two Kurdish towns in northern Syria that were invaded by Ankara and its Syrian proxies in 2019.

Turkey has threatened to carry out more military operations against the Syrian Kurds. Ankara claims that the SDF is dominated by fighters affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) - an armed group struggling for the increased rights of Kurds in Turkey.

However, with a young generation speaking Kurdish fluently in Rojava, it will be very difficult for any government to erase the language from the memories of Kurds.

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment